Trip Report

First Hammerless Ascent of North America Wall

|

Saturday June 6, 2009 8:30pm

|

|

For years it has been said that the climbing potential of El Capitan is dead and gone. With more than 80 routes and variations on the wall, some separated by only 20 feet, what new is left to do? There is plenty to do. While it may be difficult to squeeze another first ascent into the Southeast Face, there is a whole realm of possibilities waitng to be tapped.

On April eleventh Dougald McDonald and I started up The North America wall armed with a heavy arsenal of gear and tricks with the goal of making the route’s first clean ascent. The lower pitches, which were rumored to be the crux, went smoothly. The third pitch was the only section of rock on the route requiring the use of extensive fixed gear. From here the clean climbing was straight-forward with only the occasional "boulder problem" and we soon realized that all of our special gear and pins to hand-place were going to sit in the haulbag for the entire climb.

One thing we had been told again and again was that we would be dependent on fixed pins and heads. But, being the first party on the route of the season, we feared that fixed heads and pins would be coming out in our hands. This turned out to be exactly the case — many heads that looked crucial came out with barely a tug. Yet, surprisingly, these sections were all fairly easily navigated, mostly with hooks and top stepping, and this convinced us that most of the minimal fixed gear we encountered could worked around clean.

On the afternoon of the third day the skies turned gray. Fearing a storm we began racing for the summit. By nightfall Dougald and I had reached the final and crux pitch. As I began leading into a light sprinkle the climbing quickly turned hard. After only getting ten feet above the belay in a half hour on tipped out 0 cams, inverted cam hooks and #1 slider nuts, I reached a spot I felt was impassable. I was only 100 feet from the summit but I began thinking that the clean ascent was over. Then, finally, an improbable slider nut held and I was able to reach a fixed pin. With one decent piece of gear I began hooking and cam hooking the A2 Lost Arrow crack for 15 feet until I was finally able to place tipped out #0 and #1 cams. After 20 feet I was finally into A1 and shortly thereafter at the top. Being directly above the belayer, who was right above a ledge for the entire crux, the pitch was solid C4. I was only glad that it was night and I couldn’t see the landing.

By the time we topped out I had realized that clean climbing was more than just preserving the rock, it was an entirely new adventure. The final NA Wall pitch had been harder than any of the crux pitches I had led before on Sea of Dreams or Wyoming Sheep Ranch. Yet one hard pitch shouldn’t discourage future parties from doing the route clean or nearly clean. Although former nail-ups such as The North America Wall and Zodiac have gone clean, these ascents are only meaningful if future parties also leave the hammer in the bottom of the haul bag and realize that by doing so they are not only preserving the rock, but they are adding a whole new element of adventure.

Chris McNamara

Chris McNamara

|

|

About the Author

Climbing Magazine once computed that three percent of Chris McNamara’s life on earth has been spent on the face of El Capitan—an accomplishment that has left friends and family pondering Chris’ sanity. He’s climbed El Capitan over 70 times and holds nine big wall speed climbing records. In 1998 Chris did the first Girdle Traverse of El Capitan, an epic 75-pitch route that begs the question, “Why?”

Outside Magazine has called Chris one of “the world’s finest aid climbers.” He’s the winner of the 1999 Bates Award from the American Alpine Club and founder of the American Safe Climbing Association, a nonprofit group that has replaced over 5000 dangerous anchor bolts. He is a graduate of UC Berkeley and serves on the board of the ASCA, and Rowell Legacy Committee. He has a rarely updated adventure journal, maintains BASEjumpingmovies.com, and also runs a Lake Tahoe home rental business. |

Comments

Doug Robinson

Doug Robinson

Trad climber

Santa Cruz

|

|

Chris,

Clean aid is a foreign language to me. Any kind of aid, actually. I barely speak A0 bolt ladder at the "me hungry" level. But having done first clean ascents of many a free climb, with a hammer not even on the climb with us, and back before there were cams -- I can relate a little to the technique, and fully to the adventure.

Right on -- Great job! Kinda mysterious to me that "clean" and "aid" have mixed so poorly, so seldom, that a plum like the classic NA Wall could wait all those decades for you guys to pick it clean.

I hope this inspires more lazy, chisseling aid climbers to sit up in their stirrups and take notice.

Way cool!

|

|

Steve Grossman

Steve Grossman

Trad climber

Seattle, WA

|

|

Great TR Chris and way to step up to the demands of a first CLEAN ascent!

Hammer-less means no hammer once you leave the ground. It means no hammer in the haulbag or anywhere in your gear. Be clear about what is involved in that claim.

|

|

atchafalaya

atchafalaya

Boulder climber

|

|

The first "clean" hammerless (non-grossman definition) ascent was actually done in the 90's by a soloist from Truckee.

|

|

Buju

Buju

Big Wall climber

the range of light

|

|

WOW!

|

|

Toker Villain

Toker Villain

Big Wall climber

Toquerville, Utah

|

|

Did you just post this Chris?

Congrats.

Now that the bar has been raised I believe it is unethical for people to alter the route by continuing to hammer on it (besides replacing critical fixed gear).

But of course there are plenty of selfish A-holes out there that will use lame excuses to justify continuing to beat the route into submission.

I really believe that if such classic routes are to be conserved and remain viable that regulation will be required. I don't like it, but the idea of what amounts to vandalism is even less desirable.

|

|

freerider

freerider

climber

|

|

he posted this almost 2 years ago...

|

|

hoipolloi

hoipolloi

climber

A friends backyard with the neighbors wifi

|

|

Great account and insight about clean climbing towards the end.

I am not one to hesitate about using the hammer on a route when the grades and style of the route call for it. But I also feel like many of the trade routes go clean, or damn near clean, without too much effort.

I have done a few of those trade routes, and am proud that I did them clean. Of course, sometimes key fixed gear is gone and it doesn't happen. But I think the effort is important.

Grossman- Your definition and idea of hammerless climbing is asinine and absurd! That might be what hammerless means to you, but not to...well, the rest of the world.. Chris did a hammerless ascent. No hammer was used. He was completely forthcoming with the claim, per the entire worlds definition (other than yours) of a hammerless ascent.

|

|

JEleazarian

JEleazarian

Trad climber

Fresno CA

|

|

How did I miss this the first time? Nice TR. I remember reading in Rock & Ice several years ago about an ascent by Tom Frost and his son, Ryan. I was under the impression that they did the route hammerless as well. I'll need to re-read it. In any case, it's amazing to me that a route that had not had a second ascent when I started climbing, and that needed lots of rurps and knifeblades, now goes hammerless. That is progress!

Nice work, and nice TR. Thanks again.

John

|

|

survival

survival

Big Wall climber

Terrapin Station

|

|

Fail-

No pictures!!!

|

|

Clint Cummins

Clint Cummins

Trad climber

SF Bay area, CA

|

|

|

|

Feb 15, 2011 - 03:10pm PT

|

Actually, Steve is right.

"Clean" already implies no hammering.

"Hammerless" means no hammer was brought on the trip.

(This definition can be abused, because you often have something

with you that could be used to bash, like a large, heavy cam).

Just read the AAJs in the mid 70s if you want to refresh the definition.

http://www.supertopo.com/climbers-forum/445546/Bruce-Carsons-hammerless-solo-of-Sentinel-West-Face-1974

Sometimes people compromise by burying a hammer in the haulbag, so a leader is not tempted to use it except in an "emergency".

[Edit: response to hoipolloi's post below]

True, Bruce Carson's article does not use the word "hammerless".

But it is because he sort of invented the concept at that time,

and did not need a word for it yet.

It is the other articles at the time which use the word.

Here is one:

|

|

Thorgon

Thorgon

Big Wall climber

Sedro Woolley, WA

|

|

Great effort Chris & Dougald, extremely bold ascent! That is an awesome account of the upside dowm Cam Hook and #0,#1 cams tipped out, now that sounds SKETCHY!!! I know that feeling you get in the depths of your stomach as you reach and high-step in hopes of reaching something solid! I took a 40+ footer in North Carolina top-stepping and REACHING---PING and I was launched; but when that rope went taught I was certainly a happy camper!!! That's what it takes sometimes and you guys definitely deserve some praise for that type of ascent! KUDOS, Men!!!

Thor

|

|

hoipolloi

hoipolloi

climber

A friends backyard with the neighbors wifi

|

|

Actually Clint, that article makes no reference to a hammerless ascent, it only refers to a 'chocks only' ascent. It doesn't lay out a definition of a hammerless ascent. It does state he did not bring it nor pins, and liked the idea of the challenge of heading up knowing it was not an option, but doesn't define or declare what said term 'hammerless' means.

Just saying...

If we are going to split hairs per grossmans definition, might as well split em', right?

|

|

Mark Hudon

Mark Hudon

Trad climber

On the road.

|

|

|

|

Feb 10, 2011 - 01:24pm PT

|

I sorta like that actually, taking no hammer. I can't say I'll not take a hammer but I think I'm going to really, really strive to climb aid clean.

On the Shield we tapped/hammered only 8 pieces, 4 of them myself, and later, seeing how incredibly scarred the whole headwall was, I was quite bummed.

I guess If I had gone up there when the route was still considered A5, I would have been expecting to be scared shitless and have expected to suck it up and keep moving up on marginal pieces.

|

|

jstan

jstan

climber

|

|

|

|

Feb 10, 2011 - 02:16pm PT

|

Chris, our benefactor, has pretty clearly and forthrightly stated his agenda for this thread. That the problem of pin scars can actually be seen as an opportunity to make what we do an exciting chance to learn new things. Or we can turn this into yet another pissing contest by arguing, for the next 30 years, whether a hammer in the bottom of the sack rules out a "Hammerless Ascent."

We have to do better this time,

This is what is required. We cannot, yet again, let the fundamental challenge be obscured by mind numbing noise.

In the late sixties and very early seventies we faced the danger posed by the use of pins in the East, and we handled it. Doing so was easier there than in Yosemite because backing off in the East is seldom a problem. In Yosemite 25 pitches up on an overhanging wall, backing off can be a real problem. That means your challenge is extra tough. Are you all going to admit it is too much for you? You can't figure out how to solve the problem?

I seriously doubt you will.

I am not going to tell you how I think you might solve your problem. I am not a Yosemite climber. Never was. That said, those of you who wonder what the change to hammerless climbing in the East was like should read Bill Atkinson's excellent article below. It captures very well what it felt like, 40 years ago.

The 'Gunks of Yore- 1966-74

"The Clean Climbing Revolution"

-o0|0o-

by Bill Atkinson

This article first appeared in The Crux of September, 2010; a publication of the Appalachian Mountain Club, Boston Chapter Mountaineering Committee. Editors: Al Stebbins and Nancy Zizza.

It is little appreciated today that the completion of the protection revolution at the ‘Gunks preceded Ray Jardine’s introduction of the “Friend”--the first camming device--by about six years, the Tri-Cam by eighteen, and that, by the time of the publication of Doug Robinson’s “The Whole Natural Art of Protection” piece in Chouinard’s 1972 equipment catalog, it was virtually over.

In 1966 I returned to the ‘Gunks after a move from New York City to Boston and an absence from climbing of about four years. I went down with an interested friend from work and, as I drove along, I wondered whom I might greet among my old “Appie” friends at the Uberfall and whether they still hung out at Schleuter’s Mountaincrest Inn.

The changes in the area and the climbing scene were surprising and substantial. The highway had been repaved and considerably widened permitting parking on both sides along a new metal guardrail. There were many more cars than I had remembered and, at the Uberfall, a pickup truck full of climbing gear (mostly ironmongery) was parked and presided over by one Joe Donohue who had a small business going and who collected fees for and looked out informally for the property interests of Mohonk (later the Trust, and later still, the Preserve).

But what seemed most astonishing was the total disappearance of the former influence of the Appalachian Mountain Club. The Uberfall was bustling with activity but nowhere did I find a single Appie friend from four years earlier and what is more, with very few exceptions, I never, ever did. The turnover was virtually complete. Soon I made an effort to meet and establish myself with the Boston AMC climbers. Among them then: Wes Grace, Bob Chisholm, Harold Taylor, D Beyers, Bob Johnson, and Bob Hall and thus began a period of many, many years of coming often to the ‘Gunks.

The after-climbing conviviality had moved from Schleuter’s to the bar at “Emil’s” Mountain Brauhaus at the bottom of the hill, and the comforts of the inn had given way to camping out on Clove Road just beyond the second bridge over Coxing Kill. Above some open rocky slabs there was room for tents among the trees at a place that came to be known as Wickie-Wackie after a small sign on the main road advertising a bar farther down the clove. But we gave up this area in 1970 after I had a large tent stolen. Not long after that Mohonk prohibited camping there and gave the AMC, still a more or less coherent entity, permission to use the area around a small abandoned farmhouse off US 44. For many years thereafter we crashed there at the “AMC Cabin” until the Mohonk Preserve finally reclaimed it as an historic site: the Van Leuven farm.

Mohonk had also established permission for limited tenting near the Steel Bridge in an area which came to be known affectionately as Camp Slime. Years later John Ruoff, Emil’s nephew, was horrified to learn from me that “Slime” was Emil’s spelled backward.

Although there was a continuing AMC presence at the cliffs the old Club restrictions were gone. One led what he felt he could negotiate safely, and confidence in the rope was increasing. Goldline still ruled in 1970 but climbers were gaining experience with the new strong and resilient kernmantle rope introduced in the fifties in Europe and which now was gradually replacing it here. By the end of the sixties slings of knotted quarter-inch Goldline had been replaced by nylon webbing, and the bowline-on-a-coil waist tie-in was giving way to safer and more comfortable home-tied Swiss seats of the same material.

Shoes had changed to designs made by climbers specifically for the sport. There were now imported RDs, PAs, and EBs eponymously initialed by their French makers: smooth rubber soles with canvas or suede tops--greatly improved over sneakers--and kletterschue for edging and friction. Royal Robbin’s bright blue suede RRs (what else?) came along in 1971.

At first, from the point of view of the cliffs and the protection, the climbing seemed to me pretty much as it had been in 1960; leaders carried and hammered in the occasional soft iron piton where it was deemed needed and, often as not, the second left it behind--they were hard to remove and soft iron was cheap. Resident pins tended to remain in place, as before, although some were beginning to show signs of age.

The author in 1966

Joe Donohue had newer stuff in his truck; stuff forged by Chouinard in California and developed largely for the burgeoning aid routes in Yosemite. He stocked “angle” pitons made from hard chrome-molybdenum steel, in form like the softer sheet steel “Norton Smithes” of the fifties that preceded them here. The arch of the angle spread slightly, spring-like, on driving for a quick solid grip, but the grip was easily broken by a few side-to-side whacks administered by the second. Pretty easy, but--importantly--these new pins weren’t so cheap so that increasingly seconds were loath to abandon them.

Straight “Lost Arrows” were also of chrome-moly, stiff and more easily removed than their predecessors. Joe had thin “knife blades”, too, for fine cracks and the RURP (“Realized Ultimate Reality Piton”): a mere chip of steel for aid climbing via incipient fissures. Earlier, in 1961, Chouinard’s “Bongs” had arrived--the final expression of the angle concept; large pitons--some fat enough for three-inch cracks that rang with deep authority when driven “Bong, bong!” Not long after their introduction the steel version was discontinued and replaced by light-weight hard aluminum.

Gradually we updated our racks--replacing the old soft iron with the new, pricier hard stuff. My view, shared at the time by most, was to leave the occasional newly placed pin behind as a modest contribution to the general weal. Why take it out if the next one along could clip it? And so it was with shock one spring that we looked down from our stance midway up the cliff to see an approaching soloer methodically removing and racking chrome-moly. He had amassed a useful collection. It turned out to be Dick Dumais who, when challenged on this shameless lack of proper public spirit, countered that he was merely assembling his rack for an imminent trip to Yosemite.

There was, in Yosemite at first as the sixties advanced and soon at the ‘Gunks and elsewhere, a growing awareness of looming disaster--the actual destruction of the cliffs; of the cracks and small features that made climbing in any form (free or on aid) possible at all. The continued placement and removal of hard steel was having an ugly erosive effect even, we heard, on durable Yosemite granite. Piton cracks widened, even to the point where some crucial pin placement was no longer feasible. Some incipient cracks had become fingerholds.

Already locally we noticed new areas of tinted rock, long protected from the elements, where a sizeable flake had been pried off from behind; large and widening pockets, especially in horizontal cracks; and a great diminution of the fixed pin protection that had been taken for granted for years.

Voices were heard in favor of reducing piton use by adopting a suspect British tradition. The Brits had a history of eschewing pitons, not so much owing to an adverse impact on the cliffs, but simply as not really very sporting. They had become used to girth hitching slings over chicken-heads and jamming sturdy knots into vertical cracks. They filled their pockets with small pebbles to be wedged like natural chockstones and slung; and those who approached their routes along railroad tracks picked up stray machine nuts for the same purpose. Later they bored out the abrasive screw threads. Thus, the “nut” was born.

But the coming revolution was as yet unforeseen.

Early aluminum nuts began to appear; at first as curiosities and then gradually with suspect experimental value to augment placements where pitons weren’t feasible. Nuts manufactured specifically for climbing first appeared in England around 1961. Most resembled little Chinese take-out boxes, tapered on four sides. Others (Clogs, 1966) were made from hexagonal bar-stock cut to various lengths and drilled for bails. As the seventies dawned many variations appeared (Troll “Big-Hs”, Forrest “Titons”, Clog “Cogs”). Racks of pitons were more and more seen interspersed with the aluminum intruders. The small ones had braided wire bails and the large required knotted Goldline or webbing laboriously forced through the often inadequate holes provided. The wires seemed OK but the cord and webbing wanted to be as thick as possible.

Nuts of the Day

Another insult was noticed. After its introduction by John Gill, gymnast’s chalk had come widely into use and some complained of the unsightly white residue left behind on once pristine and unobtrusive hand holds; although many tacitly admitted that clues were welcome as to where previous fingers in desperation had sought a home.

Piton use continued unabated. However, a consensus was building among the environ-mentally conscious toward the absolute necessity of abandoning reliance on them before the cliffs were chipped to pieces. The result was the “Clean Climbing” revolution.

The lead was taken by John Stannard (of “Foops” fame) as it was in the West by Royal Robbins, Tom Frost, Yvon Chouinard, and others. Stannard began the publication (1971) of a newsletter, “The Eastern Trade”, devoted to the conservation of the cliffs; educated climbers by taking them up the routes with nuts; and collected old steel angles to be cadmium plated, painted a distinctive gray, and placed as permanent “residents” where all agreed they were necessary. I believe that some can still be seen on the cliffs today.

Climbers “town meetings” were called and supported by Mohonk; letters written; votes taken.

And so climbers began, tentatively, reluctantly to try nuts. Very few were falling on lead and so it was a while before safe falls on nuts became common enough to begin to engender real trust. They didn’t work well in parallel-sided cracks, and especially not well in the horizontal ones that abound at the ‘Gunks.

And then, in 1971, two game-changing events occurred: the ever innovative Chouinard came out with “Hexcentrics”, and the “All-Nut Ascents” blank book appeared on the counter at Dick Williams (new in 1970) “Rock and Snow” in New Paltz.

Because of their eccentric “hexagonal” cross-section Hexcentrics began, sort of, to solve the problem of the horizontal crack. Rotation of the shape tended to jam it in the same way that the modern (1990) Tri-Cam does so well.

The book at Rock & Snow invited climbers duly to record “First all-nut ascents” and the result was a stampede to claim the prizes. The easy routes fell early and it was less than two years before the final, hardest routes were climbed “clean.” Actually, Royal Robbins had made the first ever recorded all-nut first ascent in Yosemite in 1966. He called it “Boulderfield Gorge”, although his clean 1967 “Nutcracker Suite” is the one that became classic. By the end of 1972 the last open ‘Gunks route had fallen so that, at least among the skilled and the bold, the protection revolution was complete. Rock & Snow refused thereafter to stock pitons.

Stannard, Frost, and Robbins [Photo: Anders Ourom]

The next year Stannard published a list of all the new clean ascents with an additional rating: “a, b, or c” as a measure of the difficulty of pro-tecting with nuts and fixed pins. Out of this grew today’s familiar ratings taken from the film industry.

All right then, OK for the bold, but we more timid folk were not so sure.

By this time our own tentative pure efforts had begun. I most associate

this period with my climbing partners Sandy Dunlap, Tom Hayden, and Wes Grace--worthy nut-men all. We made our own “clean” ascents; my first, as I remember it, was “Double Chin”. “Clean” meant that we even eschewed the clipping of resident pins.

Stannard taught us how to “stack” nuts. That is, to place them in tandem with opposing tapers so that the extracting force on one caused the assembly to expand. I can remember a fascinated group at the Uberfall standing around Stannard as he worked a hydraulic jack to load a stacked set in a slightly flaring horizontal crack with an outward pull. The nylon sling gave way.

We practiced the stacking and figured out how to use two placements in opposition, each so situated as to secure the other from lifting out as the attached sling was urged upward by the moving rope, or to protect the one from being snatched in the wrong direction in a fall. We socked them in to the point where our seconds complained they couldn’t get them out. We became clever; we invited our seconds properly to admire our elegant placements before their dismantlement with the nut-pick. The pick, itself, a new development owing to the difficulty of removing jammed or hidden nuts in awkward positions, was often a homemade affair. We made picks out of kitchen spatulas and called them “nut hatches” and discovered the art of “gardening” with the pick to clean the mud and grass out of promising cracks. We mixed charcoal with chalk to dull its glaring whiteness and promoted it as “dirty chalk for clean climbing” (a lousy idea as it turned out because it sullied the beautiful, new kernmantle ropes). We modified our nuts by filing deep grooves in them and by epoxying the wire bails so that you could push on them to urge them out.

The three-nut belay anchor became our standard; we arranged equi-tension sling arrangements wherever possible.

In 1972 Chouinard came out with graded “Stoppers” and stacking became even easier. His improved “Polycentric Hexcentrics” showed up in 1974 giving us more confidence still in horizontal crack placements. Yet, we retained our doubts. For several seasons I climbed with a rigger’s energy absorption pack between my harness and the tie-in--the equivalent of the modern “Screamer”--it was supposed to rip three feet of stitches under a load of six-hundred pounds, but it never came to the test.

Increasingly the nuts seemed better than the pitons and, in general, placements could be found more often. Nevertheless, the 5.6 second pitch of “SoB Virgin” had to wait five years for the really small SLCD’s and, later, the Tri-Cam before giving up its long held reputation as a “death lead”.

Who knew that a big hex would fit the ceiling crack on “Shockley’s” and a smaller one go in behind the huge flake on “CCK”; that you could slot a perfect stopper over the bulge at the tops of “High E”, and “Madam G’s”, and on the first pitch of “Frog’s Head”; and set a large bong endwise into the off-width on “Baby”? I remember getting a huge hex to stick before the desperate under-cling traverse left just off the ground on “Moonlight”. My first under-water hex gurgled into a solution hole on Whitehorse. When an old ring-angle pulled on Cannon it was the stopper ten feet down that saved me. And how many have clipped into the long suffering resident wired stopper on “Limelight” before negotiating the delicate traverse at the top? Gradually we gained faith.

Nevertheless, while getting used to nuts, we climbed always with our hammers and a small supply of pins “just in case”. Occasionally we would clip a pin, but we had stopped placing them altogether. As Sandy recalls: “We climbed carrying pins and hammers for a long time.”, until Tom said finally, “If we don’t leave the hammers behind we’ll never get any good at this.”

And so, one morning, probably around 1974, as we started out for the cliffs, I stepped back to the car, reopened the trunk and, after long hesitation, tossed my hammer into the back. I thought that it might be my last day on earth.

We survived the day; I never again climbed with a hammer at the ‘Gunks. Our own clean climbing revolution was over.

-o0|0o-

References:

For an excellent account of this period in 'Gunks history see: Waterman & Waterman, "Yankee Rock & Ice", Stackpole, 1993, ISBN 0-8117-1633-3, pp.193-200.

See also:

J. Bernstein, “Ascending”, Profiles (Chouinard), The New Yorker, January 31, 1977.

Y. Chouinard, T. Frost, “Chouinard Equipment” (catalog), Sandollar Press. 1972.

Chouinard, catalog: http://www.traditionalmountaineering.org/book_chouinard1972catalog.htm.

J. Middendorf- http://www.bigwalls.net/climb/mechadv/index.html. http://www.bigwalls.net/climb/mechadv/index.html

Stéphane Pennequin: http://www.needlesports.com/nutsmuseum/nutsstory.htm.

Piton Antiquities- http://www.mrpiton.com/p2.

J. Stannard, “The Eastern Trade”, Vol.0, No.0, 1971- Vol.6, No.3, 1978.

|

|

scuffy b

scuffy b

climber

heading slowly NNW

|

|

|

|

Feb 10, 2011 - 02:42pm PT

|

A nice article, Thanks, John.

|

|

mongrel

mongrel

Trad climber

Truckee, CA

|

|

|

|

Feb 11, 2011 - 12:42am PT

|

I'll join the thread drift by confirming that Bill Atkinson's piece is exactly how I remember the events of that time period. But I would emphasize that the thing that really saved the rock was not whether an elite one or few parties were capable of an ascent without carrying the briefly-common hammer and few chicken pins (which only served as training aids by weighting the leader down), it was that the gear improved to a point that EVERYONE could get good pro. The hexentric helped, but I remember it being the small wired stopper that was critical to putting an end to widespread hammering in the Gunks. Likewise for Yosemite aid routes, the gear a party has or doesn't have in the haulbag does not, in real practical terms, matter for rock preservation; it's what the majority of parties actually put to use during the climb. A genuine hammerless ascent does merit much greater respect for the commitment, but the key thing for route preservation is the increasingly widespread use of offset cams and cam hooks, which effectively substitute for a lot of hammered gear.

Point of this post: a challenge to the gear manufacturers to continue to relentlessly innovate new stuff that facilitates body-weight or better placements where we now still use heads and other hammered gear. And one to all aid climbers to push their skill limits as far as possible, whether they have a chicken hammer in the bag or not.

|

|

Atkinsopht

Atkinsopht

Mountain climber

Boston, MA

|

|

|

|

Feb 11, 2011 - 12:34pm PT

|

Although I'm no longer a really active climber I maintain my contacts here with the New England climbing community.

It is my impression that the "hammerless" ethic born here in the 'Gunks- and then rapidly spread to the entire Northeast- has held firm, lo these forty years.

I think it pretty much holds still even on our puny (at 600-1,200 feet) granite walls where retreats are plenty difficult, though obviously not as challenging as those in Yosemite.

|

|

John Fine

John Fine

Trad climber

Hood River, OR

|

|

|

|

Feb 13, 2011 - 04:38pm PT

|

Rock preservation and hero preservation are different from each other, but both are important to the community.

If I had to, I'd put rock preservation first. But hero preservation has real value also.

"Clean" means avoiding damage to the rock. If the hammer is not swung, we assume that the rock cannot be damaged. Once the hammer is swung, even a little bit, we assume that the rock *will* be damaged.

"Hammerless" means avoiding the dilution of someone else's hammer-on-the-ground heroic feat by falsely claiming to repeat it *exactly as originally performed*. If I succeed at a route without swinging the hammer, but it's in my haul bag, then if I claim "hammerless", have I reduced the inspiration the community receives by looking up to the first ascensionist's true "hammerless" ascent? Or have I only offended the first ascensionist personally? We should notice that a "hammerless" ascent should include "number of fixed pieces clipped", and "number of pinscars encountered and used cleanly" to *exactly* represent the amount of heroism involved.

For myself, I feel that I can still be inspired by a first "clean" or "hammerless" ascent, regardless of whether it has been repeated using either term. But I have only been dismayed by the pin scars that I've encountered (even as I've used them!). I have swung the hammer, and I will again - but as little and lightly as I am able. It's hypocritical, I admit - but so many life endeavors involve balancing conflicting principles, don't they?

In the end it is the effect to the community that matters. I believe the safe bet is to focus on preserving the rock, because thankfully, heroism is a renewable resource.

|

|

Toker Villain

Toker Villain

Big Wall climber

Toquerville, Utah

|

|

|

|

Feb 13, 2011 - 04:46pm PT

|

I agree. The product is more valuable than the performance.

Plus we should be practical with what resources we have.

To use the fact that a route was established with a hammer, or that it was made more user friendly from hammering, or that to climb it without a hammer still requires using hammered anchors are three lame excuses that I've heard people use to continue to beat on a route that can be climbed without beating.

Myopic and selfish.

|

|

jstan

jstan

climber

|

|

|

|

Feb 13, 2011 - 05:59pm PT

|

"The product is more valuable than the performance."

When I was advised to ridicule those still using pitons I declined. If the rock was to be spared it would happen only when we all, of our own will, came together to make that happen. Ridicule drives people apart. Separating people into groups pushes them apart.

The issue of so-called "heroism" was never raised by anyone, even in the slightest. Saving the rock meant we all had to be heros. And we were. Bill's truly excellent article makes that more clear than could anything else.

If we separate people based on the presence or absence of a hammer,

we push people apart.

For no useful purpose.

|

|

Mark Hudon

Mark Hudon

Trad climber

On the road.

|

|

|

|

Feb 14, 2011 - 01:08pm PT

|

"The product is more valuable than the performance."

Wow! That's a valuable quote in this regard.

|

|

Toker Villain

Toker Villain

Big Wall climber

Toquerville, Utah

|

|

|

|

Feb 14, 2011 - 01:12pm PT

|

I'm glad somebody heard me; been saying it for decades.

|

|

hoipolloi

hoipolloi

climber

A friends backyard with the neighbors wifi

|

|

|

|

Feb 14, 2011 - 01:16pm PT

|

Great points by Ron and Jstan!

Product over performance.

I really, REALLY agree with Jstan! Well put!

|

|

jstan

jstan

climber

|

|

|

|

Feb 14, 2011 - 08:32pm PT

|

I have received this PM from John Fine, quoted here with permission.

…………………………….

"Saving the rock meant we all had to be heros."

That's what people need to see.

I chose a direct message to you here so as not to dilute the thread, but I just wanted to pass this note of encouragement to you.

I also have been following your writing on this subject via my big wall partner Mark Hudon. In my opinion, you have it right:

lifting each other up is where we find lasting happiness, not lifting ourselves up.

……………………………..

John has seen something really important to us.

In 1969 when I started working on rock damage, being egotistical, I framed it in my own mind as my doing something for others. I did not phrase it in my mind as a “lifting up” but just go with that for a moment.

Forty years later I honestly have to say I was the one lifted up. The chance to have been there to see that explosion of courage and good will has remained a source of confidence for me each day. Just to know that people can be that good.

Those walls of Yosemite are unparalleled. The people climbing them are just as unparalleled. You need to know that your defending that rock together is going to give you a quiet confidence for the rest of your life.

|

|

Atkinsopht

Atkinsopht

Mountain climber

Boston, MA

|

|

|

|

Feb 15, 2011 - 11:25am PT

|

Well said JStan; yet again.

|

|

Atkinsopht

Atkinsopht

Mountain climber

Boston, MA

|

|

|

|

Feb 15, 2011 - 01:35pm PT

|

Me again:

A cursory look at the first one-hundred or so SuperTopo forum posts tells me that there are virtually no threads dealing specifically with ethical or environmental questions related to climbing.

If SuperTopo were to institute a forum category dedicated largely (or exclusively?) to such threads, could that encourage discussion and possible action where now such (rare) threads seem of little interest or currency?

Bill Atkinson

|

|

martygarrison

martygarrison

Trad climber

Washington DC

|

|

|

|

Feb 15, 2011 - 02:03pm PT

|

I did the NA in 77. I really don't remember any fixed heads at all. We also didn't carry them. Felt it was solid A4 at the time in a few spots. Mostly I remember it being a lot of work due to traverses and overhangs.

|

|

|

|

|

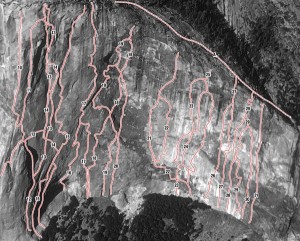

North America Wall is route number 19. Photo: Galen Rowell

Recent Trip Reports

- The Kohala Ditch Trail: 36ish hrs on foot... to and from the headwaters. [5 of 5]

May 31, 2019; 11:57pm

- A Winter Traverse of the California section of the PCT Part 8

May 31, 2019; 11:18pm

- Supertopo,A trip report for posterity

May 31, 2019; 11:00pm

- Balch Fest 2013. Two Days in and Around and On The Flake. The Official Trip Report

May 31, 2019; 10:57pm

- TR: My visit to the Canoe

May 31, 2019; 10:24pm

- Death, Alpine Climbing, The Shield on El Cap

May 31, 2019; 4:07pm

- Andy Nisbet (1953-2019)

May 31, 2019; 2:11pm

- Drama on Baboquivari Peak

May 31, 2019; 1:19pm

- Joffre + The Aemmer Couloir: ski descents come unexpected catharsis [part 2]

May 31, 2019; 7:45am

- Lost To The Sea, by Disaster Master

May 30, 2019; 5:36am

- My Up And Down Life, Disaster Master

May 29, 2019; 11:44pm

- Halibut Hats and Climbers-What Gives?

May 29, 2019; 7:24pm

- G Rubberfat Overhang-First Ascent 1961

May 29, 2019; 12:28pm

- Coonyard Pinnacle 50 Years Later

May 29, 2019; 12:24pm

- Great Pumpkin with Mr Kamps and McClinsky- 1971

May 29, 2019; 12:02pm

- View more trip reports >

Other Routes on El Capitan

|

| The Nose, 5.14a or 5.9 C2

El Capitan

The Nose—the best rock climb in the world! |

|

| Freerider, 5.12D

El Capitan

The Salathé Wall ascends the most natural line up El Cap. |

|

| Zodiac, A2 5.7

El Capitan

1800' of fantastic climbing. |

|

| Salathe Wall, 5.13b or 5.9 C2

El Capitan

The Salathé Wall ascends the most natural line up El Cap. |

|

| Lurking Fear, C2F 5.7

El Capitan

Lurking Fear is route number 1. |

|