The brass offset placement is stubborn, but I’ve got it seated at last. I clip in my aiders, give it a final test, and move upward in the steps. That’s when the first rumble of thunder, like a distant bass drum, rolls through the valley. I glance down at the belay.

“How much rope?” I shout to my partner, Joe Puryear, who is already sliding on his rain jacket and casting nervous glances up valley at the developing maelstrom.

Joe knows why I’m asking. “You’re past half rope! You gotta get to the anchor”.

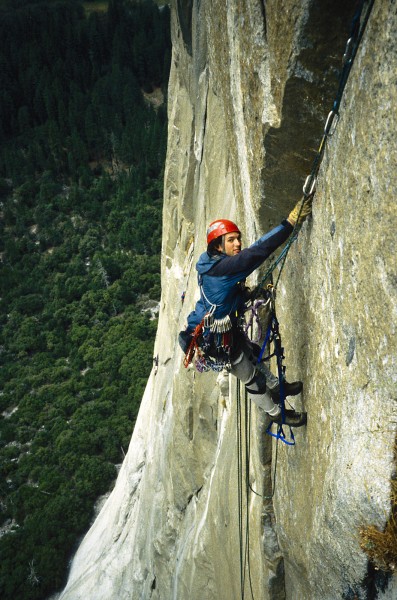

As I feared, I’m doomed to finish this pitch in the midst of an electrical storm. The 10th pitch of El Capitan’s Mescalito is in an area steep enough that the falling rain won’t quite touch us, even if trickles originating from far above and creeping down the fissures of the big stone might eventually find us and, inevitably, run into the sleeves of our jackets and soak us to the core. But at the moment, I’m primarily concerned about being hung out to dry on this string of manky A3 brassies and crappy fixed heads as thunder now cracks and booms directly overhead, accompanied instantly by blinding flashes of light. A wall of rain appears fifteen feet away from me in space, plunging away into oblivion, and gives me a momentary pause as I reflect on the sheerness of this wall.

Continued electricity manifesting around me urges me onward. I cease testing the final placements, recklessly monkeying from one sketchy piece to the next, striving for the anchors not far away. For once, I have found something that scares me more than a long fall, and that is being fried by a bolt of lightning. None of which makes any sense, of course, because reaching the anchors is not going to make the latter any less likely, and death by lightning is likely instantaneous and not fraught with the seconds of terror that come from a windmilling whipper into the void high up on the Captain.

But the illusion has successfully focused my actions. In short order, I discover that some gear placements are much stronger than they appear, and my skills at climbing more quickly and with less vigorous testing are better than I ever thought they could be. In a controlled frenzy, I finally reach the anchors, fix the line for Joe, and haul the bags. Joe jumars the line and cleans the pitch as lighting continues to streak the sky and light up Yosemite valley, darkened by the angry black clouds roiling in every direction. The wall of rain continues just out of arms reach, and it feels like I’m in one of those elegant hotel lobbies with phony waterfalls that you can walk behind.

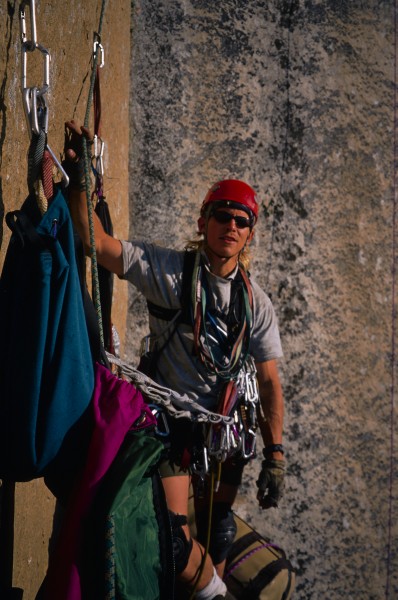

Joe and I defiantly shout invectives at the sky, deliberately over-dramatic in tone, in between the usual big wall commentary. “I can’t believe this shitty thing held your weight!” Joe muses. “So…you’re saying I’m fat?” I retort. By the time he arrives at the anchors, I’ve secured the bags, stacked the ropes, and have the portaledge partially set up. For the first time ever, we deploy the rain fly. Once inside, we close the doors and suddenly marvel at how civilized and relaxing this feels. We don’t have to worry about dropping anything; we can shut out the madness of the exposure and imagine we’re on flat ground. We fire up the hanging stove to make chili and hot soup, which is ultimately civilized. Outside it’s a williwaw storm, but we’re closed into our cocoon of illusory safety, and life on the wall is GOOD.

The storm keeps us tent bound for the remainder of the day, and the next day we move to the top of pitch 15. The Molar Traverse was a fun and memorable lead, and by the day’s end we are feeling downright confident.

For Joe and I, the fall of 1998 was our second visit to Yosemite. The previous year, in the fall of 1997, we’d made our first climbing trip to the valley. We’d climbed the Prow, the Leaning Tower, and finally Zodiac. As a youth, I’d been camping here with my dad in the summers of 1977 and 1979, without a clue that I’d one day be trying to scale these walls, and oblivious that the Camp 4 we drove past was at that very time likely occupied by many of the original stonemasters in their prime.

This fall’s trip had begun well. Joe and I warmed up by climbing the Direct Northwest Face of Half Dome. Mescalito was a route we’d dreamed about for a while: a king line that went straight up through the biggest part of El Cap’s Southeast side, but at a relatively moderate grade that, while challenging for us, we felt was an appropriate step up from what we’d done previously.

And now, fifteen pitches up, we were really getting into our groove. Neither the ominous blood stains smeared all over the middle of pitch one, the Seagull pitch with its double penji and chossy hooking, nor the myriad of sustained and tricky corners, traverses, and small roofs had deterred us.

A now-familiar predawn start is initiated as the valley’s night silence gives way to the sounds of the day’s delivery trucks rumbling up the valley road far below. “Damn”, I think, “the night always goes too fast. Time to get up”. By 7 AM, I’m happily hooking away from the anchor to take the day’s first lead, pitch 16. Fifteen feet of easy hooking brings me to an old 5/16” bolt with a Salewa hanger. Above this, top stepped, my options are suddenly limited. To my right is a shallow fold that wishes it was a crack. Or at least, I was wishing it was a crack. The crystalline sides of the corner are arranged in such a way that I’m convinced I can get a clean placement- a red alien to be precise- instead of my worst nightmare, which would be to paste a large copperhead, something at which neither Joe nor I have any real skill in doing. Multiple attempts at placing the red alien are followed by light tests which rip the piece out of the rock. I’m staving off frustration, and also the fear of the unknown, as the next several placements above this appear to be thin hooks. Finally, I get two cams on the alien seated in what appears to be a solid alignment. I test it and it holds. I carefully move onto it. Cautiously and cat-like, I climb the ladder to its top and for balance I secure my fifi hook to the placement which is now below my waist. Standing up tall I feel the rock above me with both hands. There’s no cracks here, and ten feet above me, another old bolt appears. It seems miles away. I search for the obvious hook placement that must be here. Someone must have moved it, because nothing is revealed that I like. Picking the least scary incut, which is high over my head and must be evaluated by feel and not sight, I select a hook- a cliffhanger- and try it. It sucks. At least, that’s what I tell myself to justify trying the grappling hook, just so I have exhausted all options. I replace the cliffhanger on my gear sling, and set the grappling on the edge. It seems to lever more, so it’s decided. The cliffhanger will have to do. I continue moving robotically, aware of the precarious placement I’m on so as not to dislodge it. The sling of the grappling hook is touching the oval biner and my fingers are applying the first pressure to open the gate and rack it.

A loud pop is accompanied by the sound of weightless hardware, and all at once I’m flying backwards down the rock, seemingly in slow motion. Time is suspended indeed, and what seems an eternity later, comes an impact that I did not expect. All 200 pounds of my frame meets the rock, concentrated singularly into my right leg-which has seized up and frozen completely stiff and straightened at the surprise of falling and the instant fear that arose from it. In the midst of the impact, I feel a jarring, all-consuming pain tear through my right ankle, pain which is instantly anesthetized by terror, as I feel myself rotate rapidly into a head first dive towards Yosemite Valley, 2000 feet below, and I hear myself scream. In this slowed-down sequence, my mind has time to wonder, after falling what I knew was already several body lengths, and with a bolt below me, just how and why am I accelerating? Just as I surmise that the rope has been severed and I’m surely going to become talus food, I feel a merciful, gentle deceleration. I’m inverted, and the entire big wall rack is tangled around my head as I look straight down to the trees and then, amid a wave of searing pain from my right ankle and a nauseating flood of fear and adrenaline, I let out a long anguished wail that reverberates across the valley.

Frantic, I right myself. I look at the rock and see spatters of blood everywhere. In a frenzy, I run my hands all over my head, wondering what I’ve done. Where is the blood coming from? Then I see it- I’ve cheese gratered all four of my knuckles on my right hand, taking off enormous, dime sized chunks of flesh in the process.

“MARK! ARE YOU ALRIGHT??”. Joe’s screaming jolts me out of the fog of this subsiding fear and building pain. I have fallen just past the anchor, and am over twenty feet below where I had been a moment before. Joe’s grigri is locked up, and he’s suspended in mid air, 3 feet above the anchor. I outweigh Joe by 40 pounds and have launched him several feet up, feet which added to my fall. “Tell me you’re ok so I can lower myself”, Joe pleads, and I answer.

“I’m ok, I think. But my ankle’s f*cked!”

Adrenaline is a strange thing, though. Joe sits quietly for the next few moments, watching me closely but giving me the chance to have my personal moment and then get it together. I can feel my high top boot getting tighter, the swelling cushions my injury and for a moment seems to salve the initial wave of white hot pain. Now a surge of anger bursts forth, and I stare up the rope to the 5/16” bolt 20 some-odd feet above, the only piece of gear that kept me from a factor 2 onto the anchor.

“I am going to finish this god damned pitch!” I announce through gritted teeth, directing this to the universe as much as to Joe. He allows a short moment for the absurdity of my statement to sink in, before he responds. “Can you even put weight on your leg?”

Good question. I attach my jumars to the rope, clip in an aider, and gently step into it with my right leg. I feel a dull crunch, accompanied by a bolt of pain that nearly causes me to puke and pass out.

“Nope. It ain’t gonna happen”.

I tension over to the anchor and we take stock. If I can’t bear weight, the only reasonable solution is to rappel. Oblivious to the more than a quarter mile of vertical terrain that separates us from the ground and safety, my mind jumps for a diversion.

“How am I going to afford this?” I moan, tears squeezing out of the corners of my clenched eyes. I have catastrophic health insurance but I’ve never had to use it, and I don’t know if this will be covered.

“Worry about that later. We’ve got a lot bigger problems to overcome first”, Joe counsels. Next, Joe jugs up the line to retrieve the sling and biners off of the bolt that had caught my fall.

“What is this piece of sh*t!? I have to lower off of this?!?” Joe exclaims. When I had clipped the bolt it was flush to the wall. Now, it was pulled halfway out of the rock and the shaft is bent downwards, deforming the hanger in the process.

We assess our gear, the time, and our location. The possibility of tossing the haulbag is discussed, but quickly dismissed. Beyond the obvious safety hazard to anyone at the base, we also realize that the steepness of the route beneath us and its traversing nature makes our succeeding in this descent, without assistance, far from assured. We need to keep a minimum of survival gear with us. At the least, although it’s only 7:30 AM, we might have to spend another night on the wall in order to pull this off. We do, however, decide to cut some weight by dumping all but two days of water. We also empty some food out of containers, and in the process, Joe successfully makes me forget about the pain in my ankle. He accomplished this by pouring out the bag of orange Tang drink mix. The powder flew straight up into the air above us in the morning breezes already sweeping up the wall, then drifted straight down into the pulpy wounds on my knuckles. How something like that could hurt more than a broken bone, I’ll never know, but then again, I’m kind of a lightweight on the pain threshold.

The decision is made, the adrenaline subsides, and I am focused. My ankle is still swelling but the boot seems like the ultimate splint. I can feel my toes and there’s no broken skin or deformity. I leave the boot on, take 800 mg of Ibuprofen, and I’m ready to move.

That Joe and I don’t even raise the subject of calling for help is testimony to our partnership and the trust we have built, even if, in retrospect, our decision would nearly backfire on us. In the past four years, we’d climbed dozens of routes in the North Cascades. We had climbed Denali by a remote route, made a first ascent in the Alaska Range in Alaskan winter conditions, climbed Aconcagua, and just a few months prior, we had made it far up Alaska’s Mount Huntington in desperate conditions. For the past three years, we also were working together as climbing rangers on Mount Rainier. Our trust and intuition with one another was completely in synch. We started down with eyes wide open.

The initial rappels were vertical and straight down. As such, Joe rappelled with the haulbag. It was at the top of pitch 13 when the wheels fell off. Pitch 13 is a short but aggressively traversing pitch with a roof to finish. There was no way to get back to the anchor at the top of the Molar, so we presumed that WOEML anchors would be found somewhere in the fall line below, which for a long distance was a blank, golden, dead vertical slab. Joe rappels over the roof below, which is just large enough to make the rappel a fully free hanging affair. Joe slides sixty meters down the rope before spying the bolts we’d need to reach. Joe hangs in the middle of the face, barely able to touch the wall, knots jammed against his rappel device, and assesses the 75 foot pendulum and scramble that will be required to reach the ledge. With the heavy haul bag dangling from his belay loop, Joe runs back and forth across the face. I can tell from my vantage that he’ll never make it- not with the bag, anyway. At last he latches the ledge, but another 20 feet of fifth class hand traversing separates him from the anchor. Suddenly he falls away, taking an enormous swing across the sheer face. “I’M IN TROUBLE!!” he shouts, his voice conveying raw fear. I cringe as the ropes abrade back and forth across the rounded roof edge ten feet beneath me. There are no sharp features, but the totality of the situation and the nauseating sight of this scene forces me to intervene.

“JOE! Stop. Just stop. Don’t swing anymore, the ropes are going to be damaged. You have to come back up here. We need a different tactic.”

Joe is silent, but I see him getting out his ascenders in acknowledgment. I instruct him to ascend the static line, which is effectively blocked from moving through the anchor rings by the triple fisherman’s knot joining the two ropes, but as a backup, I secure two prussik knots tightly to the static line. Both lines are loaded and there is no way for Joe to unweight them so I could fix it with a hard knot. Once he moved up and unweighted the unused line, I tied a catastrophe knot and fixed it.

As Joe ascends, I map out the new plan in my head. We will rig the lead and haul lines as a double rope rappel, but fix the lead line for Joe’s rappel. Joe will rap only the lead line on a grigri, while tied into the end of the rope for a backup, and also bring down one end of the tag line, the other end being secured to the haul bag. He’ll be hands free to perform pendulums or free climbing, and won’t have the burden of the haul bag. Then I’ll lower the haul bag to him, he can bring it in with the tag line, then I’ll do a double rope rap on the lead and haul lines, and Joe can pull me in. Lather, rinse, repeat.

When Joe arrives at the belay, he is emotionally destroyed. I’ve never seen him look so broken. He kneels on the small stance and I just put my hand on his shoulder and allow him his own personal moment. While at the bottom of the rope, prior to ascending, Joe had somehow transferred the haul bag off of his harness and attached it to the end of one of the ropes. At one point, he related, he was holding the haul bag in his hands, with it unattached to anything else. He almost let go.

Joe rises to his feet, assuming a posture that signals he’s back in action.

“You look like you have a plan. Let’s hear it”, he says, as he glances wistfully off towards Half Dome, the midday sun arcing around and beginning to kiss the sheer northwest face.

I explain what we are going to do, and Joe concurs readily. The new system is put to the test immediately, and proves a winner, as Joe easily sticks the pendulum. The bag goes down, and soon I’m clipping in next to Joe. As long as I don’t bump my foot against the rock- which happens anyway- the pain is manageable.

Down, down we go. Soon we rejoin Mescalito around pitch 9. The flow of each rappel is smooth, and we are dialed. The rock is perfectly vertical but never much more, so reaching each anchor is a simple affair.

Off to our left, Sean Easton, Pete Zabrok, and Chris Geisler have been battling up the Reticent Wall since before we launched. Our route being far easier- the Reticent at this time having less than five ascents I believe, and was the hardest route on the Captain- we had passed them over the past several days. Pete observes us rappelling by, and shouts out. “What’s going on? Everything OK?”

“We’re fine”, I answer, “but I broke my leg in a fall, so we’re bailing”.

One of them replies, “We have a phone, do you need us to call YOSAR?” Having a phone in 1998 was a very unusual thing, for the record.

“NO!” we quickly bark in unison. I continue: “We’re ok, thanks. But DO NOT call YOSAR!”

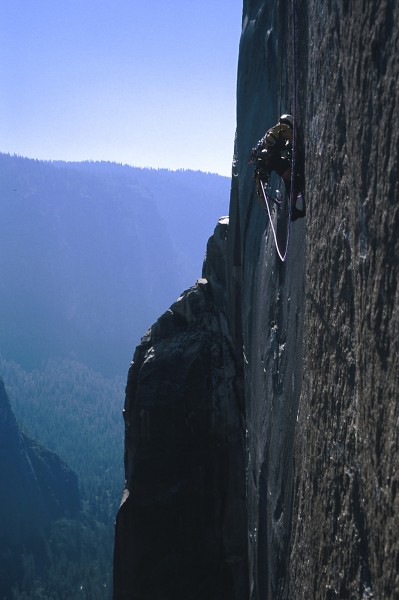

Beneath the macho bravado of two guys who work in search and rescue being too proud to call for help, I silently wonder if we are making a mistake trying to do this ourselves. This wonder is magnified by the view below me, which is of increasingly overhanging rock disappearing from view as it rolls away beneath our location. Somewhere below us is the alcove, where ultra steep routes like South Seas begin. We are very much aware of this, and are trying to remain on Mescalito for as long as possible, but we have already dismissed the possibility of reversing the Seagull, pitch 6. Now at Pitch 9, we’re going to have to cast off into the unknown before too long.

By the top of pitch 7, the corner system we are rappelling is so steep and leaning that we are faced with the inevitable choice of down aiding, or rappelling straight down and hoping to find anchors. The only route we know of between Mescalito and the Alcove is “Hockey Night in Canada”, and we have no idea about it, nor a topo. The Nose of El Cap has already cast its long shadow across the wall, which, like the sun hitting the Northwest face of Half Dome, in October, signals that the sunset isn’t all that far away.

The ground is looking tantalizingly close compared to this morning, and we’ve got the fever to get down by nightfall. We choose to commit to the void.

The first rappel is easy, and lo and behold, a bolted anchor is found. But the overhang beneath is progressively more severe. What happened next would push Joe and me into a situation I’ve never been before, and don’t ever want to experience again. Joe rappels until he sees an anchor, but it’s 10, 15, 20 feet away from him as he hangs in free space. The twelve foot long cheater stick we brought suddenly doesn’t seem like such a weenie move. I brace my body between the taut rope and the rock, and push my weight against it. I see Joe move a few inches, then I quickly release the tension, and I see Joe drift slightly back towards the rock. I repeat, cyclic, over and over, now inverted and gripping the rope with my outstretched arms. I push more and more energy into the swinging of the rope as Joe cheers me on from below, simultaneously gripping out on his increasingly wild swinging around in space 700 feet off the deck. He deploys the cheater stick and positions his body completely horizontal. “Keep going!!” he implores, as each swing towards the rock has the stick missing the anchor by mere inches. Finally he latches the bolt hanger. “GOT IT!!” The bags and I are soon reunited with Joe, and the view below is discouraging. We are, in fact, going straight down over the alcove. This may well end in defeat!

But we’re committed. Whatever this route is that we are now on- we later think it is “Space”- is by inspection, so far out of our capability that going back up is not an option, even if I could stand the pain of trying to jug or stand in aiders. Above this anchor, is a long string of heads, all of which appear to have had the wire loops deliberately cut off by some joker with a pair of metal shears- so, you get to either hook the top of the heads, or clean and re-nail the whole thing. For better or worse, Joe and I have about ten copperheads on the rack, and very little skill at using them. Therefore, the show must go on, or in this case, down.

Several more rappels commence, each worse than the last in steepness. On each one, I continue hanging upside down and tediously swinging the rope- and Joe- in an ever-increasing arc towards the anchors, taking 15-20 minutes each time, accompanied by a lot of swearing on both ends of the rope. At one point, fifteen strenuous and exasperating minutes of effort is totally undone as a gust of wind catches Joe and brings his swinging to a stop. I almost want to cry, but Joe’s plaintive encouragement keeps me going.

“You have to keep trying!!” he screams over the afternoon El Cap winds. “Ok, here we go”, I determinedly reply, and we begin again from scratch.

I keep knocking my broken leg against the rock during these operations, and especially when having to unweight the haul bag under my own power in order to lower it to Joe. One of the anchors we got to was definitely the work of another devious individual: two bolts placed just six inches above the lip of a large, 90 degree roof, which ensures that the occupants of the belay are hanging in free space, feet flailing, and tethers sawing against the edge of the roof.

The ground is getting close, and in the growing twilight I can hear the forest coming alive with the sounds of the Yosemite night critters. The bats are already swooping around us, searching for insects, and the heaviness of impending night is upon the land. Just one more rappel, right into the cave. This last anchor is marginal and so we leave behind the only piece of gear we would lose- the same red alien that had separated from the rock and initiated the events of this whole cursed day.

Joe rappels sixty meters and, with the knot on his harness jammed into the grigri, he’s suspended two feet above the slab in the alcove floor. Nearly inverted, Joe dog-paddles his hands comically, trying to make contact with the rock. Twenty feet towards the cave, it’s flat, but where he’s at, it’s steep and falls away, so coming off the end of the rope is not a safe bet. A little more swinging on my part does the trick and Joe scrambles into the cave. Soon we’re together again. From here, there’s an easy walk off climber’s right which leads to the El Cap base trail, but Joe rigs the ropes quickly and lowers first me, then the bag, into the forest another 200 feet straight down.

I relax into the talus and gravel of the valley floor and stare straight up at the behemoth of rock that we just descended. The first stars of the oncoming night sky are twinkling beyond the brink of El Cap.

I begin crawling on hands and knees, using my wall gloves and knee pads to full effect, and Joe begins shuttling the gear to the road. My mind goes into a trance and time becomes meaningless. Mental and physical exhaustion are no match for the enduring high of this kind of day, and as I continue crawling I enter a place of total calm and peace, methodically advancing down the rocky trail. Joe laps me twice, and after his final carry, he comes back through the woods from the road on the trail to the Nose and finds me exiting the last rocky part of the trail into the flat duff of the true forest floor, just a few hundred feet from the end. I have stood and am hopping across the forest floor on one leg as Joe reaches me and gives me an arm. Together, we hobble as one to the edge of the meadow, and the pavement, pausing only to laugh at that sign showing a deer kicking a boy in the face.

Now it’s eight PM, and all I can think of is a hot shower. I’m not so worried about my ankle, since I can still feel my toes and it seems positioned properly. So it’s off to the Curry Shower house, where I remove my boot for the first time since the accident. The entire sole of my foot and the medial side of my ankle is dark purple, and hideously swollen.

“Hey! That’s broken, man”, says the stranger on the next bench over.

“Ya think so, do ya??”, I reply.

Refreshed and clean, I ring the night bell at the Yosemite clinic. It’s more expensive to see the doctor now rather than tomorrow morning, so I ask for a pair of crutches and make an appointment for 8 AM.

I drive back to El Cap meadow in my old Subaru Legacy wagon, where I perform my boldest task of the day: I recline in the front seat and place my feet on the dashboard, throw a sleeping bag over me, and proceed to sleep in my car, risking an adverse encounter with the agency that I had just finished working for as a seasonal. Fortunately, no one was checking the meadow for rogue campers that night.

As I drifted off to sleep, I stole glances through the window at the dark hulk of El Cap, envious of the owners of the lights that twinkled at various places on the face, and, ever the alpinist with the poor memory and penchant for masochism, vowing already to return.

__

Post script:

Two weeks later I had surgery to place two pins in my broken medial malleolus. The procedure was successful and I was able to resume climbing two months later. Insurance covered all but $1200. A far cry from what passes for “insurance” today!

Exactly one year later, in the fall of 1999, I returned to Yosemite. Nick Giguere, Marcus Donaldson and I climbed the Shield. A week later, Joe arrived, and with Nick, the three of us jumped back on Mescalito. Fulfilling a yearlong vendetta, I led pitch 16, the scene of the accident. A fat aluminum head was already pasted where I had attempted my ill-fated cam. The rest of the pitch was a string of sketchy fixed heads and old rivets. I was psyched and relieved when I clipped the anchors, and symbolically at least, put to rest the events that had haunted my mind for the past year.

That night, we bivied sans portaledge on the spacious Bismarck ledge. Friends shouted to us from the meadow that we were going to die, and the clanging of portaledges being assembled formed a familiar and lovely soundtrack for us to enjoy a hot dinner from this magnificent perch. Once again, life on the wall was good.

A few days later, Joe, Nick and I stepped over the rim and spent a joyous night on the flat terra firma of El Cap’s summit slabs. Just three great friends in the prime of our youth, having given all that we had to the ascent.

Mark Westman