|

January

2002

Bold

School

Five of Yosemite's Most

Classic Climbs

|

From

left to right: Justin Bastien on Royal Arches, Tom Frost rappeling

Lower Cathedral Spire at sunset, and the spectacular view of

Yosemite Valley from atop the summit of Higher Cathedral Spire. |

| |

|

|

Not so long ago,

Yosemite climbers relied on belay systems that might

hold a fall, carpentry nails for protection and shoulder stands—not

bolts—to bypass blank sections. The techniques and equipment

from the 1930s would horrify a modern climber: These were

truly the days of “the leader must not fall.”

Not many of us

know what it was like to friction climb in tennis shoes without

a harness and with a hip belay or make overhanging rappels

using the Dülfer rappel method (with the rope wrapped

under the groin and over the shoulder). Today, climbers can

choose from a stunning selection of ultra-strong gear and

even download detailed route topos from the Internet. In addition

to these high-tech advantages, a modern climber who starts

a Yosemite classic knows that hundreds of others have gone

before him, and lived to spray about it.

Despite the advantages

a new-school climber enjoys, Yosemite’s towering granite

walls are still a worthy challenge. Even though we have the

luxury of knowing the rope will hold us if we fall, the exposure

and views are just as mind-blowing as they were on the first

ascent. These climbs remain the pinnacle of achievement for

any average Joe and anyone who does them will be psyched.

Even after numerous

ascents up the Big Stone, the Regular

Route on Higher Spire grabbed my attention. Following

the last pitch, I traversed under a large roof to face 1000

feet of stomach-turning exposure. Moving timidly up the

wild 5.8 arete to the summit, it was a relief that my

belayer Randy Spurrier was out of sight and could not see

my death grip on the final holds. Make no mistake, these

climbs are moderate, not easy.

Because I knew

the history of the route, the climbing experience was enriched.

Rather than an aesthetic looking rock with some good climbing,

my ascent of Higher

Cathedral Spire became a reenactment of a chapter in history.

And unlike a roped-off museum display, I was able to jam,

crimp and summit this piece of history.

|

|

|

Higher

Cathedral Spire II 5.9

It was the pinnacles, not the big faces, that appealed to

early Yosemite climbers, therefore, the Higher

Cathedral Spire, the tallest freestanding spire in North

America, was a natural attraction.

The first attempt

made in 1933 by Jules Eichorn, Bestor Robinson and Dick Leonard

was well-planned, yet lacked essential technology: they had

10-inch nails instead of pitons. This problem was solved the

following year with a hefty supply of “state-of-the-art”

gear: 55 pitons specially ordered from Europe, 13 carabiners,

manila hemp ropes and tennis shoes. The ascent was cutting-edge

in many ways: it featured one of the earliest uses of a pendulum

and was at the highest freeclimbing and aid climbing standards.

Sixty-seven years

later, Higher

Cathedral Spire remains a challenge. Unlike most rock

in Yosemite, the Southwest Face contains numerous face holds

and fractured, loose rock. The wild and exposed moves around

the “Rotten Chimney” are terrifying even with sticky

rubber and cams. Imagine navigating this pitch with tennis

shoes and ropes made of manila hemp.

|

Higher

Cathedral Spire, 5.9. |

|

Lower

Cathedral Spire – II 5.9

Though not as classic as its neighbor, Lower

Cathedral Spire is a must-do for any historical trophy

collector. Only months after climbing Higher Spire, the same

team returned to Lower Spire and started up the Southeast

Face. The route turned out to be less sustained than the Higher

Spire but more risky due to one large feature on the third

pitch: a menacing, thin flake detached ten inches from the

wall. The mindset necessary to climb the flake bordered on

insanity. First, a sharp projection on the flake was lassoed.

Then the rope, hanging vertical, was climbed hand-over-hand

until it was possible to mantel the projection. If liebacked,

the fragile flake would have broken so out came the hammer.

The leader then delicately chipped footholds into the flake

while balancing his weight in an effort to keep from pulling

the feature—and himself—from the wall. This was

Yosemite’s first instance of chipping, a practice that

was not repeated until the sport-climbing boom in the 1980s.

Today, even with

the security of modern equipment, the detached flake looks

suicidal and all climbers avoid the original direct line with

a variation to the right. The rest of the route does not have

any magnificent pitches, however, the summit and overall experience

make this a worthy outing.

|

Lower

Cathedral Spire, 5.9. |

|

Royal

Arches – III 5.10b or 5.7 A0

With the major Valley spires climbed, the pioneers of the

1930s turned to the unclimbed faces. Climbing Half Dome and

El Capitan was unthinkable. The 1400-foot Royal

Arches, however, was covered with just enough features

and ledges to forge a route.

While the first

part followed large, 4th class ledges, the upper half of the

route looked more challenging. The first difficulty, encountered

halfway up the wall, was a 10-foot blank section that was

overcome by using a “swinging rope traverse.” Even

today, 99% of climbers pendulum rather than free climb the

desperate 5.10b slab moves. A few pitches later, the climbers

encountered the second major difficulty: a gap separating

the major features. Miraculously, a dead tree trunk had formed

a perfect, albeit terrifying bridge. This feature, dubbed

“The Rotten Log”, sadly departed from the wall in

1984, removing the most classic and frightening part of the

climb. Not to worry, the route still has plenty of exciting

sections, most notably the last pitch. Here, with the easy

walk-off agonizingly close, the team faced a 50-foot blank

section covered in pine needles. Pushing the limits of friction

on polished granite with tennis shoes, the first ascentionists

pulled through a section that dismays many present-day climbers

using sticky rubber.

|

Royal

Arches, 510b or 5.7 A0. |

|

Steck

Salathé – IV 5.9

Unlike most large faces, there was no mystery in piecing together

the line that would take John Salathé and Allen Steck

up the North

Face of Sentinel: wide cracks and gaping chimneys cut

up the face from bottom to top. While such an obvious line

meant few routefinding problems, it also meant wide climbing

and lots of it.

Steve Roper refers

to the time period around the first ascent as the “technical

age.” By today’s standards, however, Salathé

and Steck used archaic gear. On a climb filled with wide cracks,

the largest piton they had were only an inch wide. They also

carried the old-school ration of water: one quart per person

per day. The climb was so difficult that Steck wondered if

there would ever be a second ascent.

Today, the route

is popular, though still considered a stout outing. For all

but the honed off-width climber, the route is solid and terrifying

5.9.

|

Steck-Salathe,

5.9. |

|

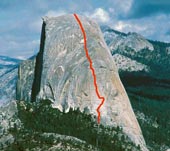

Snake

Dike – III 5.7 R

When Eric Beck, Jim Bridwell and Chris Fredericks returned

from the first ascent of Snake

Dike, the Camp 4 climbers were in disbelief. These climbers

had put up a new 800-foot route in a day from Camp 4 to Camp

4 and proclaimed the route trivial. At the time, only one

other route graced the face: the challenging 5.10b R southwest

face. According to Steve Roper, “disdain [from other

Camp 4 climbers] evolved to thoughts that the three men should

be committed.”

But, Snake Dike

first ascentionists were telling the truth. They had climbed

one of Yosemite’s most wild features: a 600-foot-long

vertical dike that rarely was harder than 5.4. Part of the

reason the team moved so fast was that they didn’t bother

to place much pro: on the entire eight-pitch climb, only six

bolts and two pitons were placed---including belays!

Fearing that they

had put up a death route for beginners, the first ascent team

gave the second ascentionist, Steve Roper, permission to add

bolts. Few modern day climbers will complain about the added

bolts as almost every pitch has a huge 5.4 runout and some

pitches have no protection at all.

|

Snake

Dike, 5.7R. |

|

Nutcracker

– III 5.8

Like most Valley climbers, Royal Robbins did not instantly

embrace nuts. For a time, nuts were thought to only be useful

in England and not the parallel-sided cracks of Yosemite.

However, after experiencing the utility and non-destructive

quality of nuts in England in 1966, Royal returned to Yosemite

a believer. Not only did he accept nuts, he set out to influence

others to stop the destructive use of pitons. What better

way to encourage nut use than to climb a first ascent using

nothing but nuts?

Not only did Royal

and his wife Liz put up a climb using solely nuts, they put

up perhaps the best multi-pitch 5.8 in Yosemite. After their

first ascent of Nutcracker Sweet (later shortened to Nutcracker),

virtually all climbers who followed only used nuts. This act

along with the 1972 Chouinard Equipment Catalog and the first

hammerless ascent of Half Dome’s Northwest Face, would

seal the fate of pitons forever.

|

Nutcracker

offers two starting lines. The right line is 5.9. The normal

start is 5.8. |

|

Details

Yosemite Valley has all the good and bad that comes with an

urban destination. The good news is that if your car breaks

down or you’re craving Filet Mignon, Yosemite has you

covered. The bad news is that it is hard to escape the car

traffic and tourists. The Valley is relatively empty from

November to April but unfortunately most long routes will

be unclimbable.

For the most detailed

topos for these routes, check out the “Yosemite

Ultra Classics” guide from Supertopo.com. Each route

comes with a detailed topo, route history by Steve Roper and

strategy section.

Many climbs require

an alpine start to avoid the crowds. Of the routes covered

here, only Royal

Arches has enough variations to easily pass slower parties.

The best time to climb these routes is in the spring and fall.

About the only time Royal Arches does not have crowds is in

the winter and early spring when much of the route runs with

water. The wet rock is not bad if you remember this key bit

of advice: take off your shoes to get better friction.

During the summer,

you will have to start at dawn to avoid the heat, especially

on the Cathedral Spires and Nutcracker. If the Valley is sweltering,

consider heading to a great swimming hole about 10 miles west

of the Highway120 entrance station. You can choose whether

to jump off the 15-foot or the 25-foot cliff. Check out the

Supertopo.com Yosemite

page for directions to get here and other swimming holes.

Other rest day

activities include filling up the cooler, renting a raft from

Curry village and floating down the Merced River. Or just

head down to El Cap meadow with a pair of binoculars and either

watch climbers or pick out the next new squeeze job (there

are still a few 50-foot sections of unclimbed rock).

If you arrive

in Yosemite in the summer, chances are Camp 4 will be full.

If you are having trouble getting a site, consider camping

next to the Merced River outside west of El Portal or at any

of the other park entrance stations. There is also more information

on extra camping on the SuperTopo Yosemite

page.

|

Yosemite

Ultra Classics provides detailed topos on Yosemite's most

classic climbs including all five of these classics, and many

more.

|

|

Chris

McNamara is the founder of SuperTopo. This article was orginaly

published in Rock and

Ice Magazine.

|

|

|